The Pervading Problems of First-World Feminism

Based on a Writing & Communications TED Talk

Preface: This article is a revised version of the TED Talk I gave for my Writing and Communications final. While one could spend years delving into the historic problems pertaining to first-world feminism, this narrative was designed to be presented within eight minutes and therefore only offers a shallow description of a few of the issues plaguing feminism into the modern day. Although there have been many communities historically marginalized by feminist practices, this article focuses mainly on homophobia and racism as they pertain to lesbians and black women respectively. The intention of this is not to ignore the struggles of other communities but to touch briefly upon some of the adversity faced by a few, specific communities. Thank you for understanding.

Content Warning: This article contains descriptions of racism and homophobia, and there are consequent mentions of violence and rape.

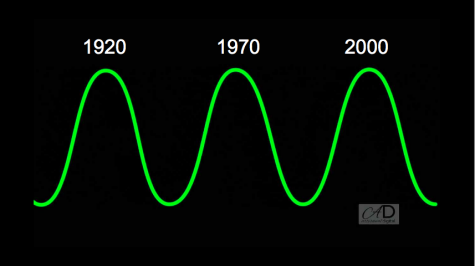

The term “first-world feminism,” refers to women’s rights activism that takes place in the more developed, western nations of our modern world. Historically, first world feminism has been broken up into large-scale movements, which we refer to as “waves” (the first wave being women’s suffrage, the second being the feminist movement that took place through the 60s-70s, the third taking place through the 90’s and early 2000’s, and so on). The problem with this model is that it disregards feminist efforts and smaller-scale movements that have taken place during the lulls, and it creates the illusion that feminism can only exist and prevail when there is a mass movement at hand.

Representation and structure, however, are far from the only problems that exist within first-world feminism. Many of the issues plaguing feminism– and hindering its progress, quite frankly– have been prevalent since the first recognized feminist “wave”: suffrage. During the early 20th century movement for women’s voting rights, racism was a large obstacle that ultimately resulted in a great deal of division. Though the passage of the 15th Amendment about fifty years prior had given black men in the United States the right to vote, many white women felt that the idea of black women voting was not as pressing of a matter. Black women were therefore excluded by many white feminist organizations and disregarded by many white feminists in general. Black feminist (such as Sojourner Truth, Anna Cooper, Ida B. Wells, and Frances Watkins Harper) began their own movements centered around the adversity that black women faced. As Frances Harper explained, “black women need the vote, not as a form of education, but as a form of protection.” In hindsight, we can see how this segregation created even more racial tension, and moreover, we see how this division between white and black feminism carries into the modern day.

In the 1960’s and 70’s, the area we refer to as the “second wave” feminist movement, there was still a significant divide between black and white feminists. The primary causes of this were the concepts for which white feminists were advocating: a woman’s right to work outside the home, for childcare, and for reproductive rights (such as abortion/contraception). Due to poverty and economic disparity, black women had been doing both domestic and out-of-house work for decades. Additionally, as activist Angela Davis wrote, “while Afro-American women and white women were subjected to multiple unwilled pregnancies and had to clandestinely abort, Afro-American women were also suffering from compulsory sterilization programs that were not widely included in dialogue about reproductive justice.” In her statement, Davis is alluding to the 64,000 African American women who were forcibly sterilized in the United States as part of eugenic programs. When I read this, words cannot even describe the level of disgust I felt– both toward our government and also toward my own ignorance. As Davis stated, these horrific occurrences were absent from the dialogue about reproductive justice back then, and they still are today. Because of those inconsistencies in perception and the lack of intercultural understanding, many black women felt alienated by the movement. Unfortunately, they were not the only ones.

Another key community that was disbarred from second-wave feminism was that of lesbians and bisexual women. Straight women viewed lesbians as a threat to the movement, labelling them as “mannish” and suggesting that their participation in the feminist revolution would hinder feminists’ ability to affect serious political change; it was assumed that the stereotype of the “man-hating lesbian” would provide too convenient of a platform upon which opposers could dismiss the feminist movement altogether. Betty Friedan, the president of the National Organization for Women during the second-wave feminist movement, argued that “lesbian issues” only posed a distraction to the causes for which feminists were fighting. Friedan dubbed lesbian feminists “the Lavender Menace,” and implied in her claims that their issues were not women’s issues– but, as lesbian feminist Judy Rebick noted, “lesbians were and always have been at the heart of the women’s movement, while their issues were invisible in the same movement,” making the ignoring of lesbians throughout the feminist campaign all the more abhorrent.

The categorizing of women– and the harm caused by it– is what led to the development of the term “intersectionality” during the third-wave feminist movement of the 1990’s. The concept of intersectional feminism is a way to encourage the idea that things such as the aforementioned “lesbian issues,” “black issues,” and “women’s issues” (etc.) are not inherently separate from one another; they intersect. While the idea of intersectional feminism is obviously the ideal, it is not always effectively practiced by today’s feminists.

Currently, we are in what would be the fourth wave of feminism if we acknowledged the wave model as an accurate method of mapping out first-world feminism. A new vocabulary term that has arisen as a result of this wave is ‘TERF,’ or, trans-exclusionary radical feminist. These are people who, whether or not they claim to be intersectional in their ideology, exclude transgender women from their activism. Over fifty transgender women have been reported as murdered since 2018, the majority of them black women. There has been little media coverage, likely due to the struggles of the trans community being deemed less important. But in categorizing these events as “trans issues,” we allow ourselves to fall back into the cycle of separating rather than unifying women to achieve total equality. Homophobia and transphobia are both still so prevalent in our contemporary society, and the misconception of trans women being “less woman” or “not real women” poses setbacks to the feminist movement, just as denying a place in the feminist movement to any community of women always has.

But TERFs are not the only problem; even today, we can still see how feminism continues to perpetuate the subliminal racism and homophobia that has been woven through the fabric of our society. I can’t help but notice that in much of the contemporary feminist discourse, the term “women’s equality” is not functioning to include all women. Take a concept as simple and familiar as the wage gap, for example. Most of us have heard by now that women make 80 cents for every man’s dollar. But this statistic (and so much of the other data being incorporated into feminist dialogue) is mostly based on the experiences of middle-aged, middle-class, white women. We seldom discuss how black women only make an average of 61 cents to the white woman’s 80. Essentially what I am trying to say is that there are people fighting for 20 cents, but their fight contradicts the founding principles of feminism– or, at least, what feminism should be– unless they account for the additional 19 cents lost by their African American peers. Furthermore, today’s feminism continues to paint a very heteronormative picture. Too many feminists advocate for healthy, balanced relationships between a man and a woman and better support for victims of domestic violence but fail to call attention to the prevalence of “corrective-rape,” or, the sexual assault/abuse of lesbians with the intention of turning them straight. In the age of “Time’s Up,” “Me Too,” and countless other movements, consent has become a large talking point for women’s rights activists; however, I do not see nor hear anyone mention the fact that lesbians– black lesbians, even more– are the largest demographic at risk of being sexually assaulted and gang raped, nor discuss how we can combat this.

And so I began to question why it took a 200-level women’s studies course at Connecticut College, a full semester of Global Issues here at Lyme-Old Lyme, an entire book by Peggy Antrobus, a TED talk assignment (and the consequent hours of research) for me to learn this information that is not widely included in today’s women’s rights activism nor the activism of the past. I came to the conclusion that the cause of all this erasure is rooted in ignorance regarding those who differ from the majority. As a society, when we encounter something that we do not understand, we too often avoid confronting it rather than taking the time to educate ourselves. This leads to invisibility (as we’ve seen) and increased “otherness” on the part of the marginalized group(s), which ultimately leads to division. It’s cyclical. If we want to truly advocate for women’s justice, we must first ensure that we are not posing an injustice to other women as the socioeconomically privileged feminists did when exploiting-the-efforts-of and then alienating marginalized women throughout the previous waves. In the modern day, it is crucial that, instead of competing over “wokeness,” we practice active introspection and identify our own areas of ignorance so that we may correct ourselves. I can assure you with first-hand experience that there is always more to be learned, but more importantly, there are always opportunities to choose whether we lift someone up or put them down. If feminists (or any activists) wish to really pour themselves into a cause and generate positive change, we must recognize that doing so requires integration, understanding, and tolerance so that we may unite our strength and act in solidarity to achieve our mutual goals.